Foraging in the Collection: William Hogarth

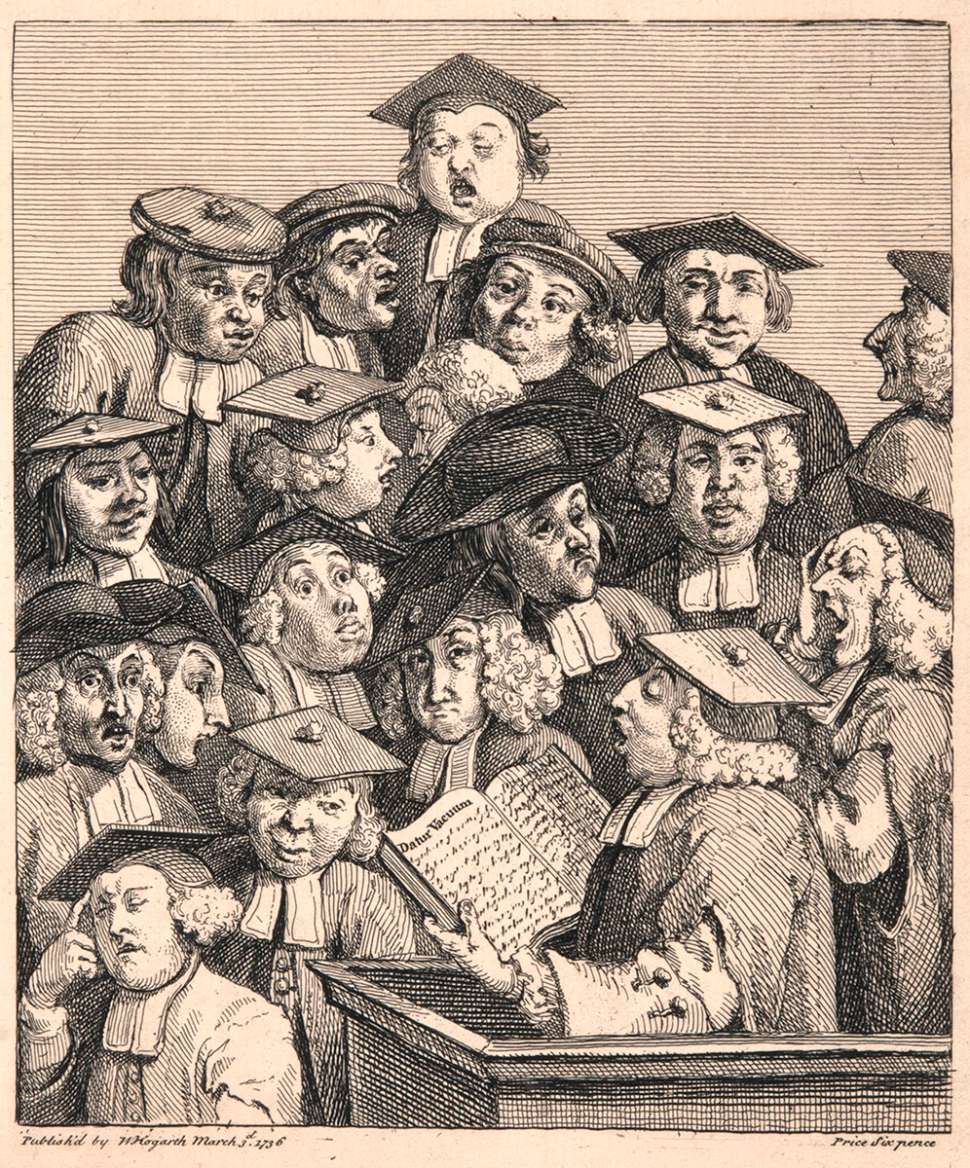

Image: William Hogarth (1697-1764), The Lecture, 1736, etching, ink on paper, 20.8 x 17.7 cm (image), 23.3 x 20 cm (sheet), Collection of Flinders University Museum of Art 164.

On the cusp of the new millennium, the exhibition One of Several: foraging in the Flinders Art Museum Collection—as Flinders University Museum of Art (FUMA) was then known—offered a snapshot of the FUMA collection to date. Featuring artworks spanning the sixteenth to late twentieth centuries, it was an exploration into the act of collecting, the idiosyncratic tastes and motivations of collectors, and the primacy of collections as ‘thinking machines’ — to borrow a phrase from Australian photographer Patrick Pound.[i]

In the opening statements of the exhibition catalogue, then-director Gail Greenwood observes: ‘As I foraged deeper, I realised what an adventure was awaiting me, what treasures were hiding in the Museum’s vaults. I began to appreciate … recent observations that the ‘art collections of … universities are a well-kept secret.'[ii]

A quarter of a century on and having recently joined the FUMA team as Senior Curator, I have the enviable task of learning about the now close to 10,000 objects in our care, constituting the second largest public collection of artworks in South Australia. It is my job to illuminate their power, insights and truth-telling, and to share the vision that artists have been sharing with us for centuries. No well-kept secrets here.

As I embark on my own foraging and begin to think through the ‘thinking machine’ that is FUMA’s collection, a foray into the earliest acquisitions reveals the work of English artist and satirist William Hogarth (1697-1764). Just last year, Emeritus Professor Norman Feather AM generously gifted A Harlot’s Progress (1732), bolstering FUMA’s existing collection of Hogarth’s most famous prints, including Marriage A-la-Mode (1745), Gin Lane (1751) and Beer Street (1759). Mirroring Hogarth’s own tongue-in-cheek style, The Lecture (1736) also makes an appearance. Entering the collection among some of the earliest works acquired, The Lecture is a rather sardonic act of collecting given Hogarth’s acerbic take on the state of the academy.

On the didacticism of art, Hogarth was a keen proponent. An eighteenth-century painter, engraver, printmaker and social commentator, his moralistic paintings and suites of narrative prints were predecessors to the modern political cartoon.[iii] His belief in the utility of art saw him adapt painted works into prints — the democratic medium. Printmaking afforded Hogarth greater distribution and reach, pitching his works at the popular rather than fine art market.

Image: William Hogarth (1697-1764), Plate 1 from A Harlot’s Progress, 1732, engraving, ink on paper, 30.2 x 37.5 cm (image), 38.5 x 45.6 cm (sheet), Gift of Emeritus Professor Norman Feather AM, 2024, Collection of Flinders University Museum of Art 6115.001.

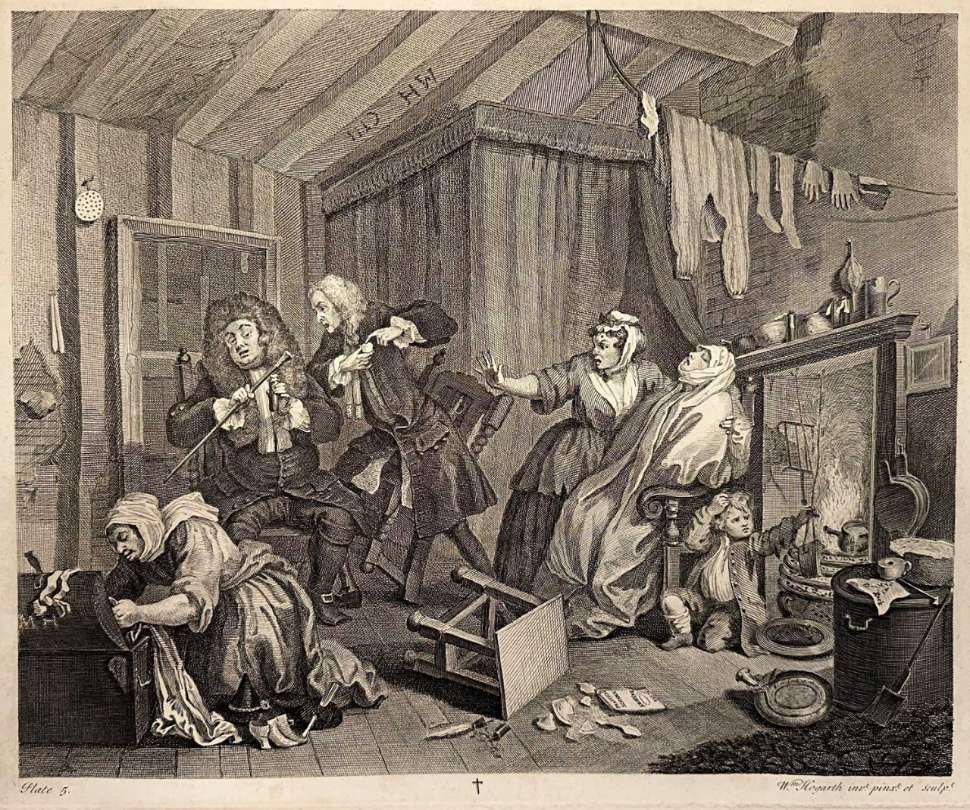

The first of his four ‘modern moral subjects’, A Harlot’s Progress tells the cautionary tale of innocence led astray.[iv] The central character, Moll Hackabout, moved from the English countryside to urban London as a young woman looking for seamstress work, as suggested by the scissors and pincushion hanging from her arm in Plate 1. However, as the title foreshadows, Moll’s fall from grace is swift. She becomes embroiled in the city’s seedy underbelly of prostitution, leading to illness, destitution and an early death.

While A Harlot’s Progress is steeped in gendered attitudes towards women in British society at the time, Moll’s story ultimately illuminates systemic struggle. Backgrounded by the Industrial and Agricultural Revolutions, when farming required fewer workers and new transport systems increased access to urban centres, A Harlot’s Progress reveals the geopolitical and social strictures of England in the Georgian era. Much like Hogarth’s later work A Rake’s Progress (1734), where we witness the rise and fall of a young man through upward class mobility, A Harlot’s Progress captures a lost struggle to change the course of one’s fortune.

In many ways, Moll’s class aspirations mirror Hogarth’s own. Hogarth straddled two worlds; he had the ‘bootstrap story of his upbringing yet eventually mingled with the most elite levels of society’.[v] Ironically, it was the popularity and widespread success of A Harlot’s Progress that liberated Hogarth from his station within his lifetime. The series was so well received that plagiarised reproductions began to circulate, spurring on Hogarth and a group of engravers to establish Hogarth’s Act, later enshrined as the Engraving Copyright Act of 1734. The Act was the first of its kind in the world to protect the rights and reproductions of artists.

As FUMA move towards its 50th anniversary in 2028, foraging in the collection and exhibition archive becomes ever more relevant. It is looking back in order to fashion the future. Hogarth is just ‘one of several’ in a polyvocal collection of histories, ideas, revelations and truths greater than the sum of its parts.

Image: William Hogarth (1697-1764), Plate 2 from A Harlot’s Progress, 1732, engraving, ink on paper, 30.2 x 37 cm (image), 38.3 x 45.4 cm (sheet), Gift of Emeritus Professor Norman Feather AM, 2024, Collection of Flinders University Museum of Art 6115.002.

Image: William Hogarth (1697-1764), Plate 3 from A Harlot’s Progress, 1732, engraving, ink on paper, 30.1 x 37.4 cm (image), 39 x 44.2 cm (sheet), Gift of Emeritus Professor Norman Feather AM, 2024, Collection of Flinders University Museum of Art 6115.003.

Image: William Hogarth (1697-1764), Plate 4 from A Harlot’s Progress, 1732, engraving, ink on paper, 30.5 x 37.7 cm (image), 39.1 x 45.8 cm (sheet), Gift of Emeritus Professor Norman Feather AM, 2024, Collection of Flinders University Museum of Art 6115.004.

Image: William Hogarth (1697-1764), Plate 5 from A Harlot’s Progress, 1732, engraving, ink on paper, 30.6 x 37.6 cm (image), 38.8 x 45.8 cm (sheet), Gift of Emeritus Professor Norman Feather AM, 2024, Collection of Flinders University Museum of Art 6115.005.

Image: William Hogarth (1697-1764), Plate 6 from A Harlot’s Progress, 1732, engraving, ink on paper, 30.1 x 37.9 cm (image), 39.2 x 45.7 cm (sheet), Gift of Emeritus Professor Norman Feather AM, 2024, Collection of Flinders University Museum of Art 6115.006.

[i] Patrick Pound quoted by Fiona Salmon, ‘Art Speaks’, Speak to Me (Flinders University Art Museum: Adelaide, 2016) 11.

[ii] Gail Greenwood, ‘One of Several: foraging in the Flinders Art Museum Collection’, exh. cat. Flinders Press: Adelaide.

[iii] Christian Dean, ‘Scholars at a Lecture: William Hogarth and Enlightenment London’, Neurosurgery, 55(2): p 436, August 2004.

[iv] ‘Plate one, from A Harlot’s Progress’, Art Institute Chicago, accessed 4 December 2025.

Belinda Howden

Senior Curator

Flinders University Museum of Art

December 2025

© Flinders University

Flinders University Museum of Art

Flinders University I Sturt Road I Bedford Park SA 5042

Located ground floor Social Sciences North building, Humanities Road adjacent carpark 5

Telephone | +61 (08) 8201 2695

Email | museum@flinders.edu.au

Monday to Friday | 10am - 5pm or by appointment

Thursdays | Until 7pm

Closed weekends and public holidays

FREE ENTRY

Flinders University Museum of Art is wheelchair accessible, please contact us for further information.