06—

David is not content to invent a wonderfully accessible, fun and effective rehabilitation device and have it just sit in a cupboard somewhere. There is only a handful of Orbys in the world. David sees the need for more. The children in the trials want an Orby in their home, so do their parents; the doctors in the stroke trial want to see Orby in clinics; Lyn would like one for her Parkinson’s SA Support Group.

Getting Orby out there

“You can have a really good idea, but it’s that next step to the market and to the user that’s the hard bit,” explained Associate Professor Sandy Walker, product and industrial designer who worked with David on the project.

To patent an idea costs about $30,000. That price increases as you extend a patent over several countries. Then comes the process of commercialisation. The problem is: as soon as you put a ‘disability label’ on a product, you might as well give up on affordability. One of David’s supervisors, neuroscientist and rehabilitation clinician Professor Susan Hillier, says, “You don’t make money out of rehab devices. If you think you’re going to make money from it, you’re a banana. Therefore, you can assume none of us are doing it for money because we’re not bananas.”

David won’t be buying that beachfront house in Waikiki any time soon. The disability market is typically small, specialised and customised. You can’t apply mass manufacturing and the commodities of scale in the same way. However, David is determined to make his creation affordable for parents.

David is passionate about how assistive technologies can benefit everyone while being fun at the same time.

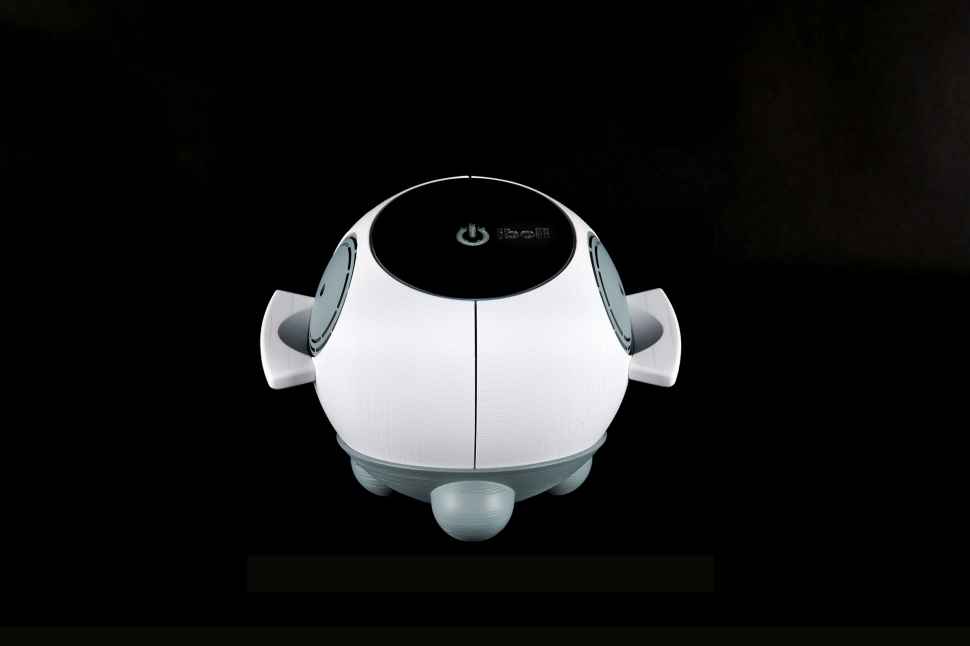

Orbit to Orby to iboll

When Orby was designed, it was intended for low volume manufacture (about 1,500 units). If it were to be a commercial product, there would be far too many components.

There are also a few issues to be addressed. For one, the first Orby needed a significant amount of cabling to connect it to a computer. If you have a hand impairment, setting up Orby could be quite tricky and you would probably need help. The newest design of Orby—which they’ve named iboll—uses a smartphone or tablet instead; there is no fiddling with cords and connectors. It uses viscoelastic materials – like the material that holds mobile phones on dashboards without flying around – so the screen doesn’t fall off, and wirelessly connects the controller to the game. As well as improving access and useability, this development reduces the components down from about 27 to nine—making it cheaper to produce. It also prevents the technology from soon becoming obsolete as the type of plugs or cords in use change. David may even experiment with colour, a suggestion from a young child when David brought Orby into his son’s class for show and tell.

Novita is a South Australian disability service organisation providing rehabilitation, therapy, community inclusion, assistive technology services to people living with disability. They support innovative research in this space and are partners for the commercialisation of Orby.

“We do research because we want to have an impact… we’ve had such good results both from evidence and from participation improvements that we know we have a product that is desirable. And so, the momentum to commercialise Orby is almost something which we can’t hold back. Families are wanting to know about it, and there are enquiries I have from overseas. People want it so we are trying to put it out there so people can buy it.”

—Dr David Hobbs, lead researcher on OrbIT project at Flinders University

The prototype for iboll, the latest iteration of Orby that harnesses mobile phone technologies such as accelerometers to enhance gameplay.

David is working with South Australian disability organisation, Novita, to commercialise the iboll, which can already be found online. At the moment, the target market is people with cerebral palsy or in recovery from stroke. However, the OrbIT gaming system could have a much broader reach.

As well as Parkinson’s, the team have also discussed uses for older people with arthritis. Because Orby and iboll don’t have buttons or require fine motor control, they could be an access point for people who struggle to use a computer mouse. They’ve also talked about how the technology could be used to control drones.

The OrbIT gaming system proves that gaming can be fun and accessible to all.

People with disabilities need not be excluded—and a great, innovative product could have myriad other uses. David’s open to, and excited about, the possibility that there may be new groups of people Orby can help too. Or commercial applications. He’s also happy knowing for people going through rehabilitation or other hard times that Orby is also just good plain fun.

LYN & THE ACCIDENTAL ENGINEER

![]()

Sturt Rd, Bedford Park

South Australia 5042

South Australia | Northern Territory

Global | Online

CRICOS Provider: 00114A TEQSA Provider ID: PRV12097 TEQSA category: Australian University